|

Frances Douglas, Lady

Douglas (1750–1817), friend of Sir Walter Scott and Lady

Louisa Stuart, was born on 26 July 1750, the sixth and posthumous

child of Francis Scott, earl of Dalkeith (1721–1750), eldest son of the

duke of Buccleuch, and Lady Caroline Campbell (1717–1794), eldest daughter

of John Campbell, duke of Argyll. She was brought up in the family's

residence at Grosvenor Square, London, where she experienced a difficult

childhood: her mother showed her little affection and was, according to

her aunt, the redoubtable Lady Mary Coke, ‘insensible to her merits’ (Letters

and Journals, vol. 1). The saving grace of her early years was her

mother's second marriage in 1755 to the mercurial politician Charles

Townshend (1725–1767). Recognizing her many qualities, he was the most

important influence on her early education and development. Alexander

Carlyle, minister at Inveresk, later a great friend and correspondent, met

her at Dalkeith in 1767 and noted her good taste, knowledge of

belles-lettres, and ready wit. He also saw how the stepfather, her

‘enlightened instructor’, protected her from the tyranny of her mother (Autobiography,

ed. Burton, 515). The growing intimacy between Townshend and the highly

strung adolescent could have developed into something more dangerous had

not Lady Frances used the occasion of her brother's marriage in 1767 to

escape to Scotland. Townshend's death some months later removed her

protector, but Lady Frances blossomed in the literary society at Dalkeith

Palace. In 1779 the death of her aunt Lady Jane Scott afforded her

financial independence as well as a house at Petersham, Surrey. Frances Douglas, Lady

Douglas (1750–1817), friend of Sir Walter Scott and Lady

Louisa Stuart, was born on 26 July 1750, the sixth and posthumous

child of Francis Scott, earl of Dalkeith (1721–1750), eldest son of the

duke of Buccleuch, and Lady Caroline Campbell (1717–1794), eldest daughter

of John Campbell, duke of Argyll. She was brought up in the family's

residence at Grosvenor Square, London, where she experienced a difficult

childhood: her mother showed her little affection and was, according to

her aunt, the redoubtable Lady Mary Coke, ‘insensible to her merits’ (Letters

and Journals, vol. 1). The saving grace of her early years was her

mother's second marriage in 1755 to the mercurial politician Charles

Townshend (1725–1767). Recognizing her many qualities, he was the most

important influence on her early education and development. Alexander

Carlyle, minister at Inveresk, later a great friend and correspondent, met

her at Dalkeith in 1767 and noted her good taste, knowledge of

belles-lettres, and ready wit. He also saw how the stepfather, her

‘enlightened instructor’, protected her from the tyranny of her mother (Autobiography,

ed. Burton, 515). The growing intimacy between Townshend and the highly

strung adolescent could have developed into something more dangerous had

not Lady Frances used the occasion of her brother's marriage in 1767 to

escape to Scotland. Townshend's death some months later removed her

protector, but Lady Frances blossomed in the literary society at Dalkeith

Palace. In 1779 the death of her aunt Lady Jane Scott afforded her

financial independence as well as a house at Petersham, Surrey.

In

1782 Lady Frances visited Dublin with her brother as the guests of Lady

Carlow, sister of Lady Louisa Stuart, but also to sort out the finances of

her stepsister Anne Townshend, who had married disastrously. For someone

who in her youth had claimed to prefer the armchair to society, her stay

in Ireland was the making of her. In a series of lively letters to her

sister-in-law, the duchess of Buccleuch, she describes herself as ‘recherchée

and fetée’, a success Lady Carlow ascribed to her having been so much

‘mortified and neglected at home’ (Stuart, Gleanings,

1.185). She stayed on to introduce her friend Lady Portland, the wife of

the new lord lieutenant, into society, returning to England via Wales,

where she visited the ladies of Llangollen, later petitioning successfully

for royal pensions for Sarah Ponsonby. Her Irish letters, subsequently

annotated by Lady Louisa, her literary executor, were, following the

conventions of her circle, never published. Like the verse journals of her

tour in Scotland in 1780, and of another to the Lake District in 1781

(written at the request of Queen Charlotte), they were copied or

circulated among friends and family, and greatly admired.

On 13 May

1783 Lady Frances married

Archibald James Edward

Douglas, first Baron Douglas of Douglas (1748–1827), at her brother's

London residence in Grosvenor Square. The marriage to a ‘safe … and

comfortable man’ seems to have been, if not a love match, one of

convenience and mutual affection. Douglas's first marriage to her friend

Lady Lucy Graham, who died in 1780, had produced four children. Lady

Lucy's attachment to her friend and Lady Frances's affection for her

children played no small part in the union, which was itself to produce a

further eight offspring. She parodied her role as ‘wicked stepmother’ in a

prose and verse version of Cinderella written in 1801. At Bothwell Castle

with its ruined medieval castle and ‘romantick solitudes’ she created an

‘air of ease, comfort and gaiety’ (Stuart, Memoire,

96), where the Douglases welcomed authors and poets, including Mary Berry

and M. G. Lewis, and the French émigré aristocracy. It was there, in 1799,

that she introduced Sir Walter Scott to her great friend and confidante

Lady Louisa Stuart, who became one of his most valued critics and one of

the few to share the secret of the authorship of his novels. Through their

auspices Scott also met the classical scholar J. B. S. Morritt of Rokeby.

She and Lady Louisa had formed a close bond through their family

connections, and a shared passion for poetry and literature. Lady

Douglas's early life is related in Lady Louisa's frank

Memoire of Frances, Lady Douglas, written some

years after her death for her daughter the novelist

Lady Caroline Scott. There she encapsulated the character of this charming

woman whom Jane, duchess of Gordon, described as ‘a most uncommon sort of

young lady’ (NA Scot., GD1/479/15/2). Lady Louisa asked Sir Walter Scott

to memorialize Frances Douglas in one of his novels, and believed he had

done so in the character of Jeanie Deans in The Heart

of Midlothian (1818).

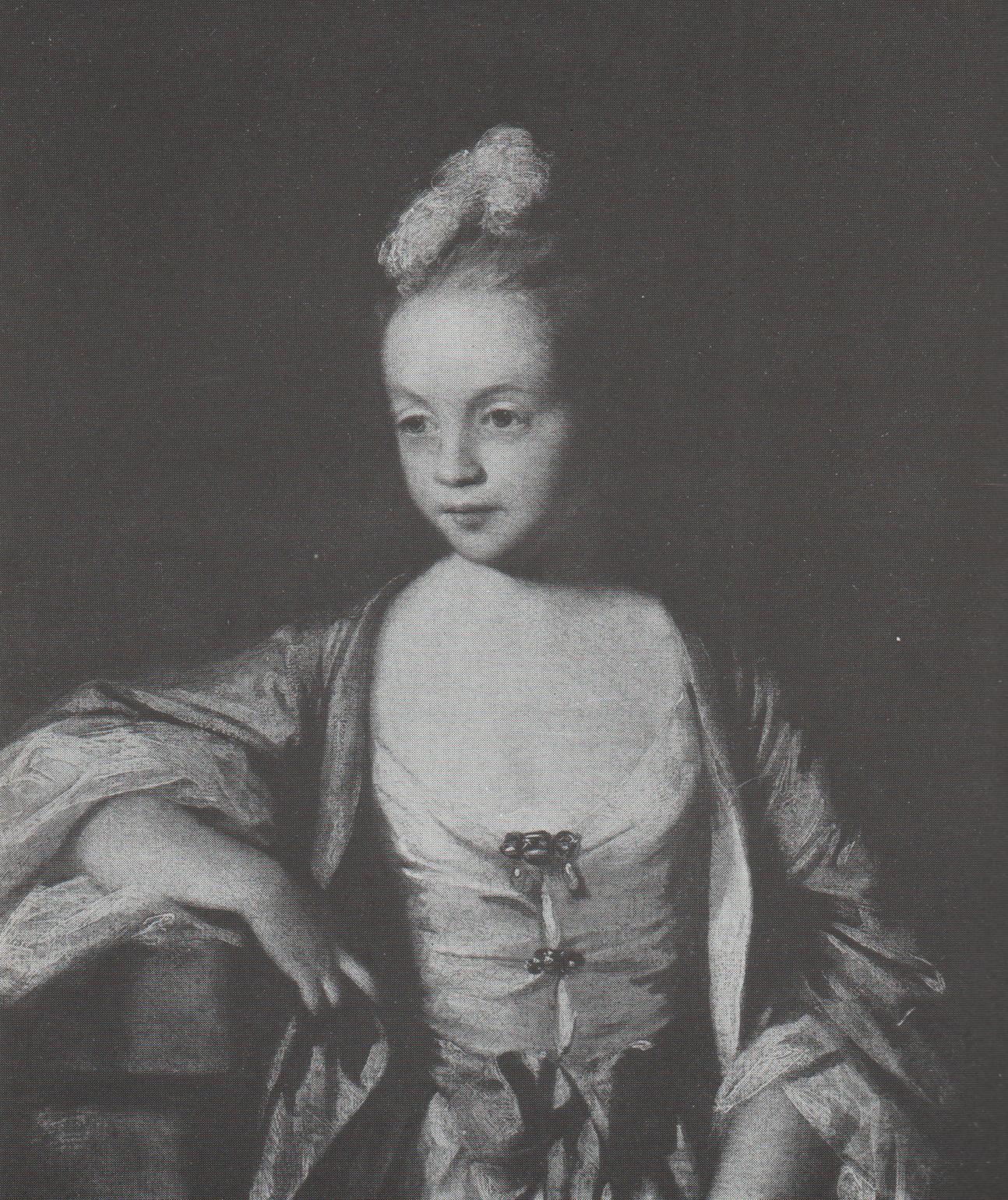

Lady Douglas was small and

undistinguished in appearance—even the favourably inclined Carlyle

described her as ‘far from handsome’—but surviving portraits of her

scarcely seem to justify Sir Walter Scott's description of her as ‘quite

the ugly old woman of a fairy tale’, though, he adds, ‘still [with] the

air d'une grande dame’. Although she characterized herself as a ‘weak,

unsteady creature’, her strength and generosity of mind, modesty, loyalty,

and wit nevertheless made her greatly admired; her only fault, mentioned

by all, was her laziness. Lady Douglas was prone to nervous exhaustion;

her many pregnancies took their toll on her health, and in middle age she

lost the sight of one eye. But her sudden death in May 1817 at Bothwell

Castle, Lanarkshire, came as a shock to her friends and family. She was

buried in the Douglas aisle in Douglas parish church, Lanarkshire.

|

|