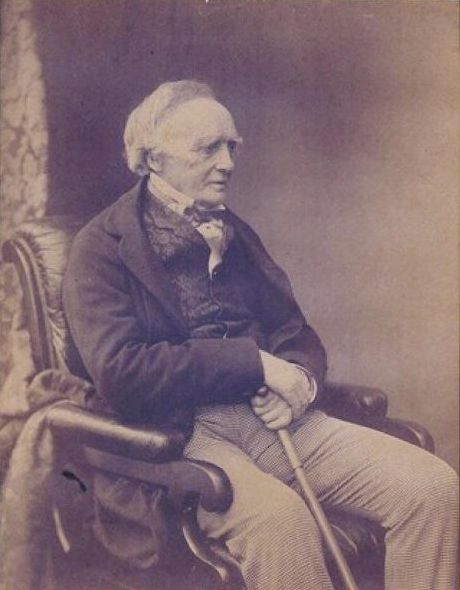

Lord William Douglas

Lord William Robert Keith Douglas (1783 – 5 December 1859) was a

British politician and landowner. He was the fourth son of

Sir William

Douglas, 4th Baronet of Kelhead and younger brother of both

Charles

Douglas, 6th Marquess of Queensberry and

John Douglas, 7th Marquess

of Queensberry.

Lord William Robert Keith Douglas (1783 – 5 December 1859) was a

British politician and landowner. He was the fourth son of

Sir William

Douglas, 4th Baronet of Kelhead and younger brother of both

Charles

Douglas, 6th Marquess of Queensberry and

John Douglas, 7th Marquess

of Queensberry.

He represented the Dumfries Burghs

constituency between 1812 and 1832 and served, on a number of

occasions, as one of the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty. He was

an active parliamentarian. He

owned sugar plantation estates in Tobago which had formerly belonged

to his father-in-law, Walter Irvine(2), whose daughter, Elizabeth, he

married on 24 November 1824. They had three sons, the second of

which, Walter, went on to continue the

Douglases of Grangemuir

line.

After William Douglas's

eldest brother succeeded to the Marquessate of Queensberry, he was

granted a patent of precedence which gave him the rank and style of

a Marquess's younger son (Lord William Douglas).

He was probably the owner of Dalhousie, in Fife.

Douglas, for whom no will has been found, died in December 1859 at

his London home in Chesham Place, survived by his wife (d. 1864) and

four of their seven children. His eldest surviving son William

(1824-68), the secretary of legation at Vienna, succeeded his mother

to the Irvine estates, took that name in 1867 and was in turn

succeeded by his brother Walter Douglas Irvine (1825-1901), who

disentailed the estates in 1872.

Lord William

is buried at Dunino, Fife, a village close to his family seat at Grangemuir, near Pittenweem.

An active parliamentarian, his full biography follows:

A London

merchant, at least until 1820, Douglas had been brought in for

Dumfries Burghs in 1812 on the joint interests of his brother

Charles, 5th marquess of Queensberry, a Scottish representative

peer, and their kinsman the 4th duke of Buccleuch. He had supported

Lord Liverpool’s administration as a pro-Catholic Tory, but

independently so, and had proved competent in debate as an advocate

of the 1815 corn law, mercantile causes and Scottish burgh reform.

The succession of the 5th duke of Buccleuch, a minor, in 1819, posed

no threat to his return for Dumfries Burghs at the general election

of 1820, but a series of letters to the Whig Dumfries and Galloway

Courier from ‘a political economist’ now warned him of the dangers

of failing to promote free trade. His parliamentary conduct in this

period was influenced by his tenure of office at the admiralty and

his marriage in 1821 to a daughter of the West India planter and

London merchant Walter Irvine, who had traded in Lombard Street

since 1798 and died in January 1824. Irvine had entrusted his Tobago

estates of Buccoo and Woodlands to Douglas and, as stipulated in

their marriage settlement, Douglas’s wife inherited Irvine’s

Fifeshire ones of Dunino, near St. Andrews, and Grangemuir House,

Pittenweem, where they later settled.

Douglas voted for

Catholic relief, 28 Feb. 1821, 1 Mar., 21 Apr., 10 May, and to

outlaw the Catholic Association, 25 Feb. 1825. He was appointed to

the revived select committees on Scottish burgh reform, 4 May 1820,

16 Feb. 1821, and defended their report and work when these were

criticized in the House by the committee’s Whig chairman Lord

Archibald Hamilton, 14 June 1821. He endorsed Lord Binning’s

amendment to the 1822 burgh magistrates bill, requiring councillors

to be resident or working within three miles of their burgh, 19 July

1822. He was against inquiring into parliamentary voting rights, 20

Feb. 1823, and opposed reform of Edinburgh’s representation, 13 Apr.

1826, insisting that no case had been made for interference with its

chartered rights or for the ‘whole principle of parliamentary reform

in its widest sense’. He voted against Lord John Russell’s

resolutions condemning electoral bribery, 26 May 1826. On the Queen

Caroline case he criticized the tactics adopted by her radical

partisans to intimidate Parliament and incite hostility to the

ministry, especially their abuse of the press, ‘unconstitutional’

mass deputations and attempts to harness ‘all grievances to the

queen’s cause’, 18 Sept. 1820. Upbraided by the presenter of the

radical Montrose petition, Joseph Hume, he reiterated his remarks

and urged ministers to act to curb the licentious press. He spoke at

the Dumfriesshire county meeting to address the king, 12 Dec. 1820;

presented two Dumfries petitions for restoration of the queen’s

rights, 26 Jan., and voted against censuring the government’s

handling of the affair, 6 Feb. 1821.

Douglas had advocated

inquiry into the distressed manufacturing districts and trades of

Scotland and elsewhere in December 1819 and he was praised by the

Dumfries and Galloway Courier and the Tory Dumfries Weekly Journal

for supporting the London merchants’ petition suggesting lower taxes

and a dual currency as remedial measures, 8 May 1820. He had

defended the petitioners’ right to promulgate what ‘they really

thought to be the sound principles of political economy and to show

how far the restrictive system of trade was contrary to those

principles’ and expressed regret at the partisan treatment of the

petition. He testified to the ‘universal feelings of surprise and

reprehension’ which the ‘extraordinary haste shown in filling up’

the vacant Scottish exchequer barony had excited and, although he

did not vote for the opposition motion condemning it, 15 May, he

supported Hamilton’s second resolution, and was applauded by the

editor of the Dumfries and Galloway Courier. He stated that he would

divide with opposition on the additional malt duty, 5 July 1820, but

if he did so, it went unrecorded. He opposed the repeal bill, 21

Mar., and voted to defeat it, 3 Apr. 1821, having defended the tax

as the ‘most general which could be selected’. He joined the

Political Economy Club in 1821, but resigned the following year. He

did not regard the corn averages as a ‘root cause’ of agricultural

distress, criticized changes to them proposed by the president of

the board of trade Robinson, 26 Feb., and joined its presenter Sir

Matthew White Ridley in endorsing a petition critical of the changes

from Leith, where he had commercial interests, 2 Apr. 1821. He

presented and endorsed the Leith ship owners’ protest against the

unfair advantage accruing to the coal traders of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

under the 1816 Act, 14 Feb. On the timber duties, he maintained that

undue preference was accorded to American produce and favoured a

variable duty on deals, 29 Mar., 5 Apr., but with immediate effect

and according to an intermediate scale, rather than after the

two-year transition period proposed, 16 Apr. He complained that

proposals to legalize game sales were a means of licensing the

disposal of stolen goods, 5 Apr. He voted against reducing the

barrack grant, 28 May, and intervened on ministers’ behalf on

supply, 15 June; but he was a teller for a motley minority of six

for increasing the compensation payment to General Desfourneaux for

his wartime West Indian losses, 28 June, brought up a petition on

his behalf, 10 July 1821, and supported others, 4 May 1829.

Douglas’s appointment to the admiralty board in February 1822, ten

weeks after his wedding and at the specific request of Queensberry

and Buccleuch’s trustees, coincided with the Grenvillite junction

with the government. A critical editorial in The Times commented:

Ministers did well to inflict this national calamity upon us in

as unostentatious a way as possible, both for the sake of their own

credit and our comfort ... The friends of the system for educating

adults for the use of the state must fervently hope, that the same

abrupt termination [of his appointment as Sir George Warrender*

suffered] will not be put to the studies of Mr. Keith Douglas, who

may otherwise, in due time, be able to aid by his learning the

ministerial writers, of the stupidity of whom, we recollect, he once

publicly complained: for when some measure was spoken of for

fettering the press, Mr. Douglas thought such a measure most

advisable; because, said he, government is brought into disesteem,

inasmuch as the journalists who write in its support are greatly

inferior in abilities to those by whom it is attacked. The friends

of retrenchment will, we trust, derive energy from even this

trifling and imperfect success.

Despite a local furore caused by

Queensberry’s libel action against the proprietors of the Carlisle

Journal, Douglas’s re-election passed without incident. He voted

against abolition of one of the joint-postmasterships, 13 Mar., but

was himself a casualty with Lord Hotham* when the House voted to

reduce the admiralty lords from six to four, 16 Mar 1822. He was

appointed to the public accounts committee, 18 Apr. On agricultural

distress, he spoke against Wyvill’s proposals for large tax

remissions, 8 May, recommended retaining a token tax on salt, 3

June, and voted in a minority of 21 for permitting the export of

bonded corn after milling, 10 June. He voted against inquiries into

Irish tithes, 19 June, and the lord advocate’s treatment of the

Scottish press, 25 June, and endorsed expenditure on a public

monument to commemorate the king’s visit to Scotland, 15 July 1822.

Irked by his loss of office, he applied to Liverpool for a place

at the treasury in February 1823, but was turned down, as were his

patronage applications to the home secretary Peel on behalf of

constituents. He voted against a proposal to raid the £7,000,000

sinking fund to finance tax cuts, 18 Mar., dismissed the wool

trade’s objections to the warehousing bill, 21 Mar., and contended

that undue importance had been attached to the regulation of the

relatively small Irish linen trade, 29 Apr. He divided with

government against repealing the Foreign Enlistment Act, 16 Apr.,

but left the House without voting on the motion for inquiry into the

prosecution of the Dublin Orange rioters when they were defeated, 22

Apr. During the inquiry, he repeatedly criticized the decision to

question Orangemen concerning their secret oaths, 8, 23 May. The

political economist David Ricardo* issued a critical review of his

speech against Wolryche Whitmore’s proposals for equalizing the

duties on East and West Indian sugars, 22 May, for he had argued

that the ‘universal application’ of the political economists’ free

trade theory was ‘not practicable’ and called on the House to heed

and safeguard the principles on which the country’s existing

commercial interests were founded. He claimed that failure to do so

and precipitate equalization in response to a temporary market

distortion caused by a glut of American sugars would ruin the West

Indian economy and its annual export trade to Great Britain and

Ireland (worth £3,560,000). He voted against investigating chancery

delays, 5 June, and the currency, 12 June, spoke and was a majority

teller for the government’s Scottish commissary courts bill, 30

June, and assisted the chancellor of the exchequer Robinson when the

distilleries bill was criticized, 8 July. He was in a minority of 20

against the barilla duties bill, 13 June, and voted against

repealing the usury laws, 17 June. As agent for Tobago, which he

never visited, he presented its legislature’s petition complaining

of economic distress, 18 July 1823.

Douglas’s appointment to

the standing committee of West India planters and merchants, 9 Feb.

1824, which he addressed that day as a supporter of the chairman

Charles Rose Ellis* and of Canning’s November 1823 standing orders

on slavery(1), postdated Irvine’s death and coincided with his return

to the admiralty. His re-election, 4 Mar., when he chaired a grand

dinner and made a speech on the constitution, which his critics

rightly deemed ‘incomprehensible’, was unanimous. On 16 May he

confirmed his support for Canning’s slavery resolutions and joined

him in expressing regret that Fowell Buxton, whose speech that day

catalogued specific cases of slave abuse since 1795, had not

‘abstained from all irritating topics’ that prevented temperate

debate. He added that, with the possible exception of Jamaica, the

colonial assemblies were being brought into line and, like Tobago,

legislating to improve the treatment and welfare of slaves.

Following lord chancellor Eldon’s declaration that the Equitable

Loan Company (of which Douglas was a vice-president and director)

was ‘illegal within the operation of the Bubble Act’, 4 Feb. 1825,

Douglas endorsed the Bubble Act repeal bill and claimed that in

Scotland the Act was already a ‘dead letter’, 2 June 1825.

Attending to Scottish and constituency business, he presented

petitions against the silk duties from St. Andrews, 17 Mar., against

taxing notaries’ licences from Dumfriesshire, 23 Mar.,

Kirkcudbright, 29 Mar., and the county, 23 Mar., and from Dumfries

to safeguard its salmon fisheries, 8 Apr. 1824. He was in favour of

proceeding with the government’s Scottish judicature bill without

the additional inquiry proposed by Hamilton, 30 Mar. He presented

petitions from Dumfries and the county for repeal of the tax on

shepherds’ dogs, 8, 9 Apr., and revision of the licensing laws, 4

May; from Annan and its presbytery against the proposed alteration

in the duty on hides and skins and against the Scottish poor bill,

24 May 1824, and from Leith for the release of bonded corn for

consumption, 28 Apr. 1825. The 1825 lowlands churches bill was

entrusted to him, 30 May, and he assisted with the Scottish

partnership societies bill, 22 June 1825. He defended the

admiralty’s decision to remove naval officers who took holy orders

from the half-pay list, 22 Feb., and brought up the report and

amendments to the officers at sea bill, 5 Apr. 1826. He privately

opposed the government’s decision to extend the inquiry into the

circulation of bank notes under £5 to Scotland, but justified his

decision not to vote against it, 16 Mar., on the grounds of the

system’s ability to withstand scrutiny. He warned that Scottish

petitions were almost unanimously against change, pointed out that

the argument for interference was flawed, as the English would not

accept small denomination Scottish notes in preference to their own

specie, and said that confining inquiry to a few selected

institutions would place individual companies at risk. He presented

a hostile petition from Dumfries, 10 Apr. Resisting pressure to the

contrary from the presbytery of Dumfries, he endorsed the

government’s West Indian policy, 1 Mar., and voted against

condemning the Jamaican slave trials, 2 Mar. He presented

anti-slavery petitions from Kent, 20 Apr., and Cupar, 11 May 1826,

praying for planters’ interests to be considered in the event of

abolition. His return at the general election in June was assured,

and from his grace and favour apartment at the admiralty he assisted

John Norman McLeod* in his abortive quest for a seat. Before

Parliament assembled in November, he consulted Henry Brougham*

concerning the Crichton bequest for a new university at Dumfries,

and the colonial under-secretary Wilmot Horton about Robinson’s

dispute with the legislature of Tobago and the transfer of their

agency, which he had surrendered formally, 21 Jan. 1826, to Patrick

Maxwell Stewart*.

Douglas was the government’s representative

on the election committee that considered the Leominster double

return and took charge of the 1827 Scottish bankrupts bill. He

divided for Catholic relief, 6 Mar., and was a spokesman for the

Scottish Dissenters in discussions on the Test Acts, 14 May 1827.

The king revived the office of lord high admiral for his brother the

duke of Clarence when Canning became prime minister, and the

admiralty board went into abeyance. Douglas was included on

Clarence’s council and, as one of his spokesmen, he defended the

appointment of commanders to ships of the line to improve naval

discipline, 30 May, and justified building work at the entrance to

the admiralty to accommodate carriages, 13 June, and Clarence’s

controversial promotions system, which included commissions by

purchase, 21 June. He divided with his colleagues against the Penryn

disfranchisement bill, 28 May, and the Coventry magistrates bill, 18

June 1827. During the recess, he attended the Portsmouth dinner in

honour of Clarence, and was reappointed by the Goderich ministry to

his council. Party feeling ran high in Dumfriesshire at the 1827

burgh elections and celebrations marking the coming of age in

November of the 5th duke of Buccleuch, as whose stooge ‘Mercator’

[John Gladstone*] portrayed Douglas in the local press. In forming

his ministry in January 1828, the duke of Wellington ignored

suggestions that Douglas’s removal from office would ‘give umbrage

to the Buccleuch connection’, and Douglas, who now took a house in

Eaton Square, never forgave the duke for the public humiliation of

being forced out to make way for Lord Brecknock*. Although excluded

from the finance committee (his name had featured on the master of

the mint Herries’s list), he refused to join in the opposition to

the navy estimates proposed by his former colleague Sir George

Cockburn, 11, 12 Feb. His failure to vote to repeal the Test Acts,

26 Feb., when he left the House before the division, provoked a

local debate on his suitability as a Member, which his readiness to

present favourable petitions, 24 Mar., 17 Apr., did little to allay.

From Dumfriesshire he presented petitions against the malt duty, 29

Feb., the stamp duty on receipts, 4 Mar., the settlement laws, 6

May, and the Scottish courts bill, 15 May. He voted for Catholic

relief, 12 May. The chancellor Goulburn ridiculed as unworkable

Douglas’s proposal for extending the provisions of the small notes

bill to Scotland to assist the cattle trade, 16 June. He in turn

opposed the measure to the last, dividing in the minority of 13

against its third reading, 27 June. Seconding Wilmot Horton’s motion

for papers on the Demerara and Berbice manumission orders, 6 Mar.,

Douglas explained that his support for Canning’s 1823 resolutions

was undiminished and, drawing on Coleridge’s ‘Six Months in the West

Indies’, correspondence from naval commanders and statistics from

captured slaving ships, he strove to demonstrate that France and

Spain were sustaining the slave market to the detriment of British

West India planters and traders. He presented a petition stating

this from planters resident in Edinburgh, 9 June, and, citing from

it, reiterated his plea for gradual amelioration and criticized the

abolitionists for arguing their case simplistically on the moral

issue of the ‘indisputable rights of man’:

As to the

compensation to the slave proprietors, I own ... I could never

acquire any intelligible idea as to what is meant by it. The mere

market price of the slaves surely would not be a sufficient

compensation ... The House would do better in confining its views to

the practical amelioration of the condition of the slaves as far as

the state of society and the circumstances of our colonies will

admit.

Douglas stewarded at dinners in honour of Buccleuch’s

first visit to Dumfries in October 1828 and was instrumental with

Lord Garlies* in reviving the Dumfries and Galloway Club of London

early in 1829. As the patronage secretary Planta predicted, he voted

for Catholic emancipation, 6, 30 Mar., and he presented favourable

petitions, 20 Mar. He also attended to his constituents’ hostile

ones, and by equating the legal status of Scottish synods and

presbyteries to those of English archdeacons and their courts, he

was instrumental in securing the receipt of that signed by the

moderator on behalf of the presbytery of Dumfries, notwithstanding

its prior rejection by the Lords and the procedural objections

raised by Charles Williams Wynn, 30 Mar. He brought up others

against the Scottish gaols bill, 7 May, and for ending the East

India Company’s trading monopoly, 14 May. The general meeting of

West India planters and merchants, 8 Apr., appointed Douglas to the

subcommittee that chose Lord Chandos* as their chairman, 13 May, and

he deputized regularly for Chandos on delegations to the board of

trade and became one of the West India Association’s chief spokesmen

in the Commons. He also supported Charles Grant’s unsuccessful

motion for a 7s. reduction in the duty on sugars, which he urged

ministers to consider seriously before the next session, 25 May

1829.

He accompanied William Burge* and Chandos to the

treasury for pre-session talks with Wellington, Wilmot Horton and

Goulburn on the commercial crisis in the West Indies, 16 Jan. 1830,

and pressed ministers relentlessly that session for information, a

full inquiry and concessions to assist the planters. Endorsing their

distress petition, 23 Feb., he testified to the losses and reduced

incomes of ‘British’ West Indian families since the abolition of

slavery in 1807 and to the inability of British planters and

merchants to compete with their French, Spanish and American

counterparts, able to replenish their workforce with slaves in their

prime. His spirited justification, later that day, of the West

Indians’ petition for better administration of justice infuriated

the colonial secretary Sir George Murray, who had trouble refuting

his claims that offices had been left unfilled. Citing from papers

ordered, 17 Feb., and his Association’s petition, he pressed their

campaign for lower tariffs on coffee and sugars, 19 Mar. His

announcement on 19 May that he and Chandos would seek a full inquiry

by select committee, the papers and statistics he had ordered (7, 8

Apr.), and the representations he made to Herries, as president of

the board of trade, on behalf of the bankrupt merchant banker Jonah

Barrington, prompted Wellington to urge Herries to confer with

Goulburn, Murray and Peel to ensure that Douglas was prevented from

‘bringing the issue to a committee of the House of Commons during

the present session’, or at least from doing so independently. On 18

May, to taunts from Hume that he had bowed to government pressure,

he postponed his inquiry motion pending Peel’s investigation into

the Barrington case. He headed a West Indian deputation to the

treasury on the matter, 29 May, and presented the Glasgow West India

Association’s petition against equalization of the duty on spirits,

12 June. He soon perceived that Chandos’s motion for reductions in

the sugar duties was doomed, and remarked caustically that Goulburn

should apply his ‘wait and see’ strategy to duties on their rum and

other spirits, 14 June. Setting aside mistrust and his private

preferences, he spoke for Huskisson’s amendment to reduce the duty

on West Indian sugars to 20s., deeming it similar enough to

Chandos’s, 21 June. He failed to have the matter deferred to avoid

defeat and when, in view of the small government majority (161-144)

and George IV’s death, Goulburn announced a reduction to 24s., 30

June, his complaints that this was less than the West Indians

deserved were disowned by Huskisson and went unsupported. He

objected to the government’s handling of the West India spirits bill

and strongly backed Huskisson’s abortive proposal for a reduction to

5s. 10d. a gallon in the duty on rum in Scotland and Ireland, 5

July. He ordered returns and presented the Glasgow West India

proprietors’ petition for legal protection for their English and

West Indian holdings, 9 July. Objecting on the 13th to Brougham’s

‘ill-timed’ slavery motion, he refused to debate the ‘abstract

question whether man may be the property of man’ or to ‘defend

individual slave-owners’, and failed to turn the discussion to

Canning’s resolutions and West Indian property rights. He voted for

the enfranchisement of Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester, 23 Feb.,

and against making forgery a non-capital offence, 7 June. Drawing on

his departmental knowledge, he criticized proposals to amalgamate or

abolish the office of treasurer of the navy to which Thomas

Frankland Lewis* had been appointed, 12 Mar., and testified to

recent improvements in accounting practices there, 30 Mar. He

presented and endorsed petitions against renewing the East India

Company’s charter from Pollokshaws, 8 Apr., Annan and Dumfries, 20

May 1830.

The anti-slavery lobby (represented in the Dumfries

and Galloway Courier by ‘Presbyter’) and the earl of Selkirk’s

coming of age, 22 Apr., had made Kirkcudbright and the Burghs harder

to manage. At the 1830 general election Douglas, who fretted over

his wife’s imminent ‘confinement’ (she gave birth to a daughter on

17 Aug.) and corresponded with Buccleuch throughout, canvassed

assiduously and was obliged to keep a high profile in the county and

the Stewartry to secure an unopposed return. He refused to pledge

his future parliamentary conduct. He corresponded with the board of

trade on West Indian issues before Parliament met.54 Calling on

Brougham to make his anti-slavery motion, scheduled for 25 Nov.,

‘less abstract’ and ‘more specific’, 8 Nov., Douglas pointed to the

denominational nature of most of the petitions supporting it, 8, 11,

23 Nov., and, replying to Lord Morpeth, he portrayed the planters as

defenders of the slaves’ interests, 23 Nov. 1830. The Wellington

ministry counted him among their ‘friends’, but he divided against

them on the civil list when they were brought down, 15 Nov. He

described retrenchment and civil list reductions as ‘useless’ unless

the populace were employed, 9 Dec., and objected to ‘striking off’

recipients of civil list pensions indiscriminately ‘as the king’s

revenue was involved’, 23 Dec. In a definitive speech, 13 Dec., he

endorsed a distress petition from the West India planters seeking

inquiry into the ‘whole state of society in the West Indies’ and the

slave owners’ right to compensation. He complained that prejudice

made it impossible for the West India interest to ‘put their case

fairly’ and, warning of the damaging effects of unrest and trading

losses, he asked ‘whether precipitate abolition would really help

the African’:

I became a West Indian proprietor about eight

years ago by succession. By the laws of my country I became

responsible for the proper management of this peculiar property. Had

I immediately manumitted my people, all industry would have ceased

on my property, and they would have become vagrants - a nuisance to

every neighbouring proprietor ... I thought it my duty to agree to

the resolutions of 1823, rather than to adopt any other course; and

I thought time would be given until a manifest improvement had taken

place in the condition of the slave.

Turning to reform, which

Queensberry was ready to support, he conceded that it was necessary

‘to a certain extent’ but ‘most pernicious and mischievous, if it is

to prevent Members from deliberating freely and fairly on the

affairs of this country, and to enter into pledges that cannot be

fulfilled, without committing the greatest injustice’. The general

committee of West India planters and merchants had commended ‘the

persevering diligence and consummate ability’ Douglas had ‘displayed

in the protection of the interests of the West India colonies’ as

chairman of the acting committee, 8 Dec. 1830, and despite resigning

from it, 30 June 1831, he deputized for Chandos at meetings as

hitherto, negotiated terms for inquiry with the board of trade, and

ordered returns preparatory to drafting papers on the sugar duties.

After discussing opposition tactics with Peel and Herries, Douglas

denounced Lord Althorp’s budget as ‘confused’ and ‘incomplete’, 11

Feb., and described the proposed tax on stock transfers as a ‘breach

of trust’, attributable to the first lord of the admiralty Sir James

Graham*, 14 Feb. Seconding Chandos’s relief motion, he delivered his

usual mantra on colonial ruin and incompetent government policy, 21

Feb., but despite their success in engaging the vice-president of

the board of trade Poulett Thomson in debate, they made little

progress. Douglas repeated his claims in discussions on trade, 11,

18 Mar., and the sugar and timber duties, 15, 22 Mar., and again

when opposing Buxton’s slavery abolition motion, 15 Apr. 1831, but

he now substituted age-specific population totals for trade

statistics.

He called for a separate Scottish reform bill, 3

Feb., and warned on bringing up a Dumfries petition, 4 Feb. 1831,

that his constituents would only accept a ‘measure which takes seats

from Cornwall to restore them to Scotland’. He successfully moved an

amendment for information on Scottish burghs with populations of

2-4,000, 3 Mar., and contended when details of the Scottish measure

were announced, 9 Mar.

that the present arrangement of

districts can no longer be continued under a reform system. To a

close system it was well enough adapted, but it will be found

cumbersome under the proposed bill. And when each individual of the

constituent body has the privilege of a direct vote, I fear the

arrangement of districts will not only be cumbersome, but

excessively expensive.

He divided against the English reform

bill at its second reading, 22 Mar. Next day, he addressed the

‘provost, magistrates, council, trades and other inhabitants of the

Dumfries District of Burghs’, where two reformers were canvassing

and his brothers’ support for him was doubtful. Confirming his

future candidature, he strove to justify his hostile vote:

[The bill] had not undergone any previous public discussion, nor was

its probable working or consequences made familiar to men’s minds by

that private deliberation in ordinary society which is the safest

mode of maturing any measure for public adoption. I therefore did

and do see so many hazards to be incurred, by suddenly changing the

whole balance of our present system of government, by displacing 168

English Members from that constituency which has hitherto returned

them, transferring 106 of these to counties and large towns, and

cutting off 62 Members entirely ... I tell you truly as an honest

man I could not bring my mind to vote by acclamation for the

principle of a measure that had so extensive an operation. Many

gentlemen have voted for the second reading with a determination to

cut down the principle of the bill by striking out its clauses in

the committee. I have considered that I was taking a more manly and

straightforward course in acting as I have done. A measure such as

the one now before the country cannot be trifled with. If a wrong

step be taken it cannot be retraced; and this constriction has had a

strong influence on my decision.

In the House, 30 Mar., 12

Apr., he objected to hurrying the Scottish measure through, cast

doubt on its suitability, notwithstanding the widespread support for

the extended franchise proposed, and poured scorn on ‘the whole bill

mantra’. Knowing that he had ‘delicate cards to play’, he approached

Buccleuch, who enabled him to see off an attempt, supported by

Queensberry, who denied it, to replace him with his brother Henry, a

reformer. After assisting with his canvass at Easter, Buccleuch’s

agent Thomas Crichton commented, 10 Apr., ‘If there is no change in

the law, Mr. Douglas I think will succeed. If the present bill

passes he will not have the least chance’. The Times, which later

described him as a ‘person of great pretensions’, observed, 18 Apr.:

Mr. Keith Douglas may well declare [that] the spirit of reform

that pervades the country is attended with great inconvenience. To

be met with the groans of the people, is very disagreeable, - to be

burnt in effigy is not at all flattering. A narrow minded man ...

who feels that he is soon to lose his political consequence, must

behold with alarm the expression of honest popular feelings.

To Lord Ellenborough and fellow anti-reformers, Douglas’s absence

from the division on Gascoyne’s wrecking amendment, 19 Apr. 1831,

was ‘shabby’. However, it encouraged reports that he was ‘for the

bill’ and briefly assisted him at the ensuing general election.63

Targeted by radicals whom he claimed were encouraged by the

pro-reform Dumfries Courier, he considered his success ‘very

doubtful. If I am back in Parliament to assist in keeping in order

many of the projects that are afloat, I must I suspect find a seat

in England’. He also deemed his return impossible without military

assistance to quell the Dumfries mob. Queensberry as county lord

lieutenant provided this and, belatedly assisted by his brothers

John and Henry, he carried the Lochmaben delegate’s election and so

secured his return. To Buccleuch, whose candidates in Dumfriesshire,

Linlithgow Burghs and Selkirkshire he now assisted, Douglas

observed: ‘My success is a great triumph. My intention is to use it

with every moderation and I shall tell my constituents that they

shall have future access to me as if nothing had occurred’. He had

recently been appointed a deputy lieutenant of Dumfries and

Fifeshire, where, as praeses, he facilitated the return of the

anti-reformer James Lindsay the following week.

He presented

and defended the Forfarshire anti-reformers’ petition, 27 June, and,

opposing the reintroduced reform bill at its second reading, 6 July

1831, condemned it as a destructive measure, devoid of a safety net,

that struck at the ‘existence of every institution in the country’.

He attributed the Wellington ministry’s defeat and the ‘current

sweeping reform’ to the duke’s refusal to concede the

enfranchisement of large towns and said that he had been prepared to

support the bill’s enfranchisement proposals (schedules C and D) and

a £10 or £15 franchise in the new constituencies, but nothing

further until this change had been properly evaluated. Challenging

ministers to explain the difference between towns of 2-4,000 and

6-7,000 inhabitants, he spoke scathingly of the schedule B

disfranchisements and complained that the bill deprived West Indians

of parliamentary influence and that the Scottish bill failed to

provide equal and adequate representation for Scotland. He voted for

adjournment, 12 July, to make the 1831 census the criterion for

English borough disfranchisements, 19 July, and to postpone

consideration of the partial disfranchisement of Chippenham, 27

July. He repeated his objections to schedule B, 2 Aug., disputed the

case for enfranchising Gateshead, which he claimed to know well,

independently of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 5 Aug., and supported

petitions against the proposed disfranchisement of the Anstruther

Easter Burghs, 6 Aug. Unwell with ‘influenza’, he learnt with dismay

that Queensberry, who had gone over to government, was determined

not to return him again and, fearing an early dissolution, he turned

again to Buccleuch. He joined in the criticism of the three Member

English counties and pressed for second seats for the Welsh

counties, Aberdeenshire, Ayrshire, Fifeshire, Forfarshire,

Lanarkshire, Midlothian and Perthshire, 13 Aug. He refused to commit

a premature vote for Hume’s scheme for colonial representation, 16

Aug. He presented Kirkudbright’s petition requesting a transfer to

the Wigtown district of burghs, 23 Aug. He objected to using

Saturday sittings to expedite the reform bill’s progress, 27 Aug.,

voted against disfranchising non-resident freeholders of Aylesbury,

Cricklade, East Retford and New Shoreham, 2 Sept., and maintained

that two-day polls would be unmanageable in Yorkshire and the large

metropolitan constituencies, 5 Sept. He also voted that day to

suspend the Liverpool writ. He divided against the English reform

bill’s passage, 21 Sept., but for the second reading of the Scottish

bill, 23 Sept. Before doing so, he spoke of his longstanding

conviction that some reform was necessary in Scotland, his

reluctance to give the impression, by a hostile vote, that he

opposed all change, and his deep and persistent objections to the

ministerial measure as it stood. He devoted much of his speech for

Murray’s proposal to grant two Members to Aberdeenshire, Ayrshire,

Fifeshire, Forfarshire, Lanarkshire, Midlothian, Perthshire and

Renfrewshire, 4 Oct. 1831, to pleading for the continued separate

enfranchisement of Selkirk and Peebles. He now also challenged

Althorp to state the likely electoral effects of permitting the

eldest sons of Scottish peers to sit for Scottish counties and,

receiving a fudged reply, protested that ‘reform’ had not been

thought through.

Douglas chaired the West India planters and

merchants’ standing committee in St. James’s Street, 19 June 1831,

and represented them in discussions at the treasury and board of

trade on molasses (to which select committee he was appointed, 30

June), the sugar duties and the beleaguered sugar refinery bill. He

presented the Dublin West India Association’s petition against

renewing the Refinery Act, 30 Aug., and when the renewal bill was

delayed, 5 Sept., he moved unsuccessfully for a committee on the

commercial, financial and political state of the West Indies.

Opposing the bill’s committal, 12 Sept., he protested that ministers

had kept him uninformed and criticized Althorp’s policy of

permitting foreign sugars to enter the country for refining and

re-export, so keeping prices at continental levels, below the

British West Indians’ production costs. He failed to have ‘the

statements, calculations and explanations, submitted to the board of

trade, relating to the commercial, financial, and political state of

the British West India colonies, and printed by the House of Commons

on 7 Feb. 1831’ referred to a committee of the whole House. As a

minority teller, he harried ministers when the refinery bill was

held over, 13, 14 Sept., and the report presented, 28 Sept., pressed

again for inquiry 30 Sept., and on 6 Oct. was named to the committee

conceded on West Indian commerce, to which he immediately submitted

evidence in writing.70 His opposition to the ‘vexatious’ sugar

refinery bill persisted, but his objections, requests for deferral

and attempts to kill it failed, 6, 7, 13 Oct., and exposed divisions

within the West India lobby, 13 Oct. In November he wrote to the

president of the board of trade Lord Auckland and Brougham setting

out his own views on the sugar trade. He recommended ‘opening the

trade on a system of duties and drawbacks’ determined by the country

of production, and suggested

that the duty on British

plantation sugar should be 15s. per hundredweight; East India sugar,

the actual growth of any of our residences in India 18s., and

foreign 20s. I would further suggest that they should all be

admitted for consumption in this country at these distinctive rates

of duty, on condition that all such importations shall be made in

British ships; and that the slave trade shall be effectually

abolished in the foreign countries to which this privilege shall be

extended.

Partly on account of his West Indian commitments,

he prevaricated over going to Scotland to rally support for the

anti-reformers following the English bill’s defeat in the Lords. He

divided against the revised bill at its second reading, 17 Dec.

1831, and committal, 20 Jan., and against enfranchising Tower

Hamlets, 28 Feb., and the third reading, 22 Mar. 1832. He again

poured scorn on Gateshead’s case for separate enfranchisement, 5

Mar. According to Lord Ellenborough, Douglas frequented the Carlton

Club during the crisis of May when the king’s invitation to

Wellington to form a ministry failed.73 Riled by the popular reform

petitions that the episode prompted, he criticized the Edinburgh one

presented by the lord advocate, Jeffrey, 23 May, and accused

ministers of refusing to treat the question of Scottish reform with

‘fair deliberation’ from the outset. Justifying his remarks, he

added:

At my own election, because I professed my honest

opinions and refused to vote for ‘the bill, the whole bill and

nothing but the bill’, there were persons in conjunction with

government who took care to suppress anything like deliberation; and

this has been the case at all other public meetings, whether the

object was to petition Parliament to elect a representative. We have

now reached the stage where the power of the king and ... Lords is

entirely superseded. Under these circumstances I have made up my

mind as to the Scotch reform bill. I consider it quite unnecessary

to offer any suggestions respecting it, because it is well known the

government will admit of no alterations. We now have a ministry, not

only invested with their known customary official power, but also

with the power of the king and both Houses of Parliament. It is,

therefore, better to leave to them all the responsibility and

inconvenience that must attend on a measure carried in so

unconstitutional a manner.

He divided against the Irish

reform bill at its second reading, 25 May, and called for a uniform

freeholder franchise, 2 July. He wanted to see a combined Greenock

and Port Glasgow constituency under the Scottish reform bill, 15

June, and was a minority teller that day against the dismemberment

of Perthshire. He divided against government on the Russian-Dutch

loan, 26 Jan., 12 July, and expressed surprise at the failure of

Alexander Baring’s bill denying debtors parliamentary privilege, 13

July 1832.

Douglas was included on the revived West India

committee, 15 Dec. 1831, and, testifying before them, 2, 3 Feb.

1832, he spoke candidly of his eight to ten years’ experience as an

absentee planter and produced accounts from his estates for scrutiny

that confirmed his tenet that the absence of protective tariffs and

the age-structure of post-abolition British plantations adversely

affected their competitiveness. He suggested introducing a drawback

on West Indian sugars and permitting rum to be refined and rectified

in bond.74 Their deliberations had little effect on his

parliamentary conduct, but the delays to the report infuriated him.

With Chandos, he pressed for tariff concessions on dark and clay

sugars, information on the ministerial relief measures and a full

debate, 29 Feb., 7, 9, 14, 15, 23 Mar. He protested at delays to the

West India committee’s report and to the crown colonies relief bill,

and criticized the government’s reluctance to discuss West Indian

issues in a full House and their prevarication and ‘ambiguity’ on

policy, 28 Mar., 13 Apr. He remained convinced that Fowell Buxton’s

policies would ‘destroy the colonies at a stroke’ and conceded that

he had been ‘caught out’ by the late change in the wording of his

motion for a select committee to consider the West Indian reports

and the immediate appointment of a select committee on slavery, and

also by the colonial under-secretary Lord Howick’s willingness to

grant it, 24 May. He now criticized Fowell Buxton’s choice of

statistics, and he was dismayed to find that his appeal to Canning’s

1823 resolutions as a common rallying call went unheeded. On the

crown colonies relief bill, which he opposed, 13 June, 3 Aug., he

played second fiddle to the Jamaican agent Burge, with whom he was a

minority teller, 3 Aug. He succeeded in harrying Althorp on

commercial issues, the differences between crown and legislative

colonies and the remit of previous orders-in-council, 20, 27 July, 3

Aug.; but when, assisted by Holmes, he tried to have the issues he

had then raised and papers he had ordered on colonial labour, 2

July, and crown colonies, 27 July, referred to the new West India

committee, he failed by 51-20, 3 Aug. 1832.

As expected,

Douglas stood down at the dissolution in 1832, and although mooted

as a likely Conservative candidate for St. Andrews Burghs in 1835

and the Dumfries district in 1839, he did not stand for Parliament

again. He remained active at the Carlton and in West Indian circles,

welcomed Peel’s decision to repeal the corn laws and corresponded

with Brougham, whose legal advice he had first sought in 1833, when

his late father-in-law’s (and thereby his family’s) rights to the

Irvines’ Scottish and West Indian property became the subject of

costly and protracted litigation in the court of session and Upper

House, which ultimately ruled in their favour, 2 Aug. 1850. He

attributed to Brougham personally William IV’s decision to grant him

and his siblings the precedence of younger sons and daughters of a

marquess. Douglas, for whom no will has been found, died in December

1859 at his London home in Chesham Place, survived by his wife (d.

1864) and four of their seven children. His eldest surviving son

William (1824-68), the secretary of legation at Vienna, succeeded

his mother to the Irvine estates, took that name in 1867 and was in

turn succeeded by his brother Walter Douglas Irvine (1825-1901), who

disentailed the estates in 1872.

Notes:

1. According to the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership at the

University College London, Douglas was awarded a payment as a slave

trader in the aftermath of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 with the

Slave Compensation Act 1837. The British Government took out a £15

million loan (worth £1.43 billion in 2020) with interest from Nathan

Mayer Rothschild and Moses Montefiore which was subsequently paid

off by the British taxpayers (ending in 2015). Douglas was

associated with three different claims he owned 576 slaves in Tobago

and received a £10,907 payment at the time (worth £1.04 million in

2020)

2. Walter Irvine planter of Tobago came back

to Britain in 1796 and bought an estate in Surrey. Died there in

January 1824. He left a large estate in Scotland, possessed by Lady

Douglas, his daughter, by virtue of her marriage settlement.

Any contributions will be

gratefully accepted