James (The Gross), 7th Earl of Douglas

James Douglas, 7th earl of Douglas and 1st earl of Avondale, and of

Balvenie, [called James the Gross], (c1371 - 1443), was the younger

son of Archibald the Grim (3rd

Earl of Douglas) Douglas (c.1320–1400), and Joanna Murray, lady of Bothwell

and Drumsargard (d. after 1401).

James Douglas, 7th earl of Douglas and 1st earl of Avondale, and of

Balvenie, [called James the Gross], (c1371 - 1443), was the younger

son of Archibald the Grim (3rd

Earl of Douglas) Douglas (c.1320–1400), and Joanna Murray, lady of Bothwell

and Drumsargard (d. after 1401).

His exceptional rise to

dominance in his family and in the kingdom began with the disastrous

defeat of his elder brother,

Archibald Douglas, fourth earl of Douglas, at

Homildon Hill in 1402.

After the capture of the earl and his leading followers James was

left to maintain Black Douglas influence in southern Scotland. He

deputized for the earl as warden of the Scottish marches and keeper

of Edinburgh Castle, but

when he tried to maintain his family's position found himself

increasingly challenged by a rival faction in the south led by

Robert III's councillors, Sir David Fleming and Henry Sinclair,

second earl of Orkney. Most worryingly for James, Fleming's and

Orkney's support of the rebel Henry Percy, first earl of

Northumberland, created tensions with England which led to attacks

on Douglas lands and jeopardized negotiations for the earl's

release. In early 1406 these tensions resulted in open conflict.

James Douglas led a force from Edinburgh which caught Fleming,

Orkney, and the young heir to the throne, the future James I, in

Haddingtonshire. Orkney and Prince James escaped by sea, but Fleming

was killed by Douglas's men in a running fight.

James

Douglas's success preserved Black Douglas dominance in the south.

Between 1406 and the release of his brother in 1409 he managed the

family's interests in the kingdom. He supervised the demolition of

Jedburgh Castle in 1409, and the governor of Scotland, Robert

Stewart, duke of Albany, recognized his significance by calling him

‘our lieutenant’ in 1407. Despite this importance James was never

more than his brother's deputy and, when the earl returned to

Scotland, James assumed the role of councillor to his senior kinsmen

which would continue until 1440. His service to the earl brought

rewards, albeit in a form which suggests a certain wariness on the

latter's part. The grant of estates in 1408 included Balvenie in

Banffshire, Avoch in Inverness, Aberdour in Buchan, Petty and Duffus

in Moray, and Strathaven and Stonehouse in Lanarkshire, and without

much doubt represents an attempt to direct James's interests and

energies to the north. This appanage was created from the

inheritance of James's mother, Joanna Murray, but in terms of

James's future interests the earl's most notable grant to his

brother was Abercorn Castle in

Linlithgowshire. For the rest of his life Abercorn was James's

principal residence. Between 1408 and 1424 it served as a base for

his plundering of the Edinburgh and Linlithgow customs and as the

basis for connections with the neighbouring Crichtons and

Livingstons, which would later be of vital importance.

During

this period James Douglas remained a councillor of his brother and

in the early 1420s he acted as the link between the earl and Murdoch

Stewart, duke of Albany, the new governor. Although there may have

been plans for him to marry into the Albany Stewarts, James

Douglas's links with the duke did not prevent his appearing as a

councillor of James I when the king returned in 1424, and he was on

the assize which condemned Albany and his sons in 1425. In these

roles Douglas acted in his family's interests, but his marriage

(before March 1426) to Beatrix Sinclair (d. in or before 1463),

daughter of his former enemy the earl of Orkney, cemented his own

connection with the royal council, and the king quickly appreciated

the importance of Douglas's support for his relationship with

Archibald Douglas, now fifth earl of Douglas, who was the nephew of

both men. In 1426 James received royal confirmation of his lands at

a time when the king was putting pressure on the earl, and in

1430–31, while his nephew was briefly imprisoned by the king, James

replaced him as warden of the west march and remained a royal

councillor. This backing from the earl's senior kinsman was vital to

the king to prevent a clash with the Douglas affinity, and in the

1430s James received continued royal favour. His eldest son, William

Douglas, was knighted by the king in 1430 and by 1435 he himself was

sheriff of Lanark, confirming his place among the king's principal

followers.

Despite the often difficult relationship between

the king and the earl of Douglas, James Douglas successfully

maintained his place in family councils and, when, in 1437, the king

was assassinated, he transferred his support to the earl. Along with

two other Douglas adherents in royal service, Sir William Crichton

and John Cameron, bishop of Glasgow, James backed the earl's

appointment as lieutenant-general for the young James II, contrary

to the expectations of James I, who had planned that in the event of

his death his wife, Joan, should act as regent. Return to family

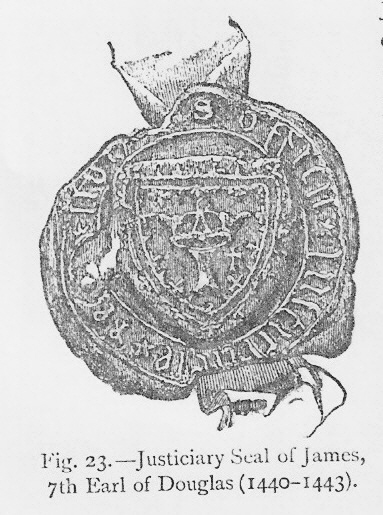

loyalty paid James Douglas well. Within months he was made earl of

Avondale and justiciar, and, with his grateful nephew in power, he

was guaranteed an influential role on the lieutenant's council.

Along with Crichton, he probably engineered the downfall of Bishop

Cameron in April 1439, further securing their place in government.

This security was shaken by the death of the fifth earl of

Douglas in June 1439. Though James acted for his great-nephew

William Douglas, sixth earl

of Douglas, the future was now threatening. James's influence in

the minority government and in the Douglas family were both at risk,

the first from Queen Joan, the second from the new Douglas earl.

Characteristically, both problems were resolved in James's favour by

force applied by his allies with no certain guilt being attached to

Douglas himself. In August 1439 the queen was arrested by Sir

Alexander Livingston in Stirling Castle and released only when she

surrendered her son, the king. Douglas was present throughout and

had well-established links with Livingston. The settlement, which

gave custody of the king to his ally, safeguarded Douglas's

interests, and he produced his great-nephew to seal the agreement.

Over the next year it was this great-nephew who caused James

anxiety. Earl William was a potential rival who would soon have the

lands and men to back any claim to his father's lieutenancy. James

was no more prepared than Livingston and Crichton to risk this

dominance and on 24 November 1440 Earl William and his brother,

David, were arrested and executed at a feast in Edinburgh Castle.

The deed was carried out on the direct order of Crichton, but to the

chief advantage of James, who at the same time took the opportunity

to remove Sir Malcolm Fleming, a close associate of the sixth earl

who was also a local rival. This ‘Black Bulls Dinner’

left James as heir by male entail to the Douglas earldom and,

together with the coup of 1439, made him the most powerful figure in

the kingdom.

In spite of his career as a royal councillor it

is significant that, as seventh earl of Douglas and lord of

Lauderdale, James concentrated on family aggrandizement, leaving

custody of the king to Crichton and Livingston. The new Douglas earl

sought to create a network of lands and alliances which was not

limited to the southern interests of his predecessors. He directed

his younger sons towards north-east Scotland. His third son,

Archibald, was married to Elizabeth Dunbar, coheir of the earldom of

Moray, and in 1442 was created earl of Moray. Archibald's twin

brother, James Douglas, the

future ninth earl of Douglas, was chosen as bishop of Aberdeen in

1441, a mark of his father's influence with the conciliar party,

though the appointment proved ineffective; after the elder James's

death his two youngest sons, Hugh and John, were provided for from

his own northern estates. Earl James clearly intended to implant the

Douglas family into the disturbed political society of the north. In

the south he followed a similar course. In Berwickshire he

intervened in a complex feud within the Hume family. His principal

aim was to re-establish the influence exercised by his brother in

the east march before 1424. James did not ignore the traditional

territorial interests of the Black Douglases. Before his death he

probably arranged the marriage of his eldest son, William, future

eighth earl of Douglas, to Margaret, sister of William, the sixth

earl. To achieve this he had to obtain a papal dispensation. Through

this match Galloway, which James did not inherit, would be reunited

with the earldom. By inclination and experience, Douglas was not a

border magnate like his predecessors. His main residences at

Abercorn and Lanark confirm him as a magnate whose lands and

personal connections centred on Clydesdale and Lothian. The

marriages of his daughters to landowners in these two sheriffdoms

support this impression. It was thus appropriate that it was at

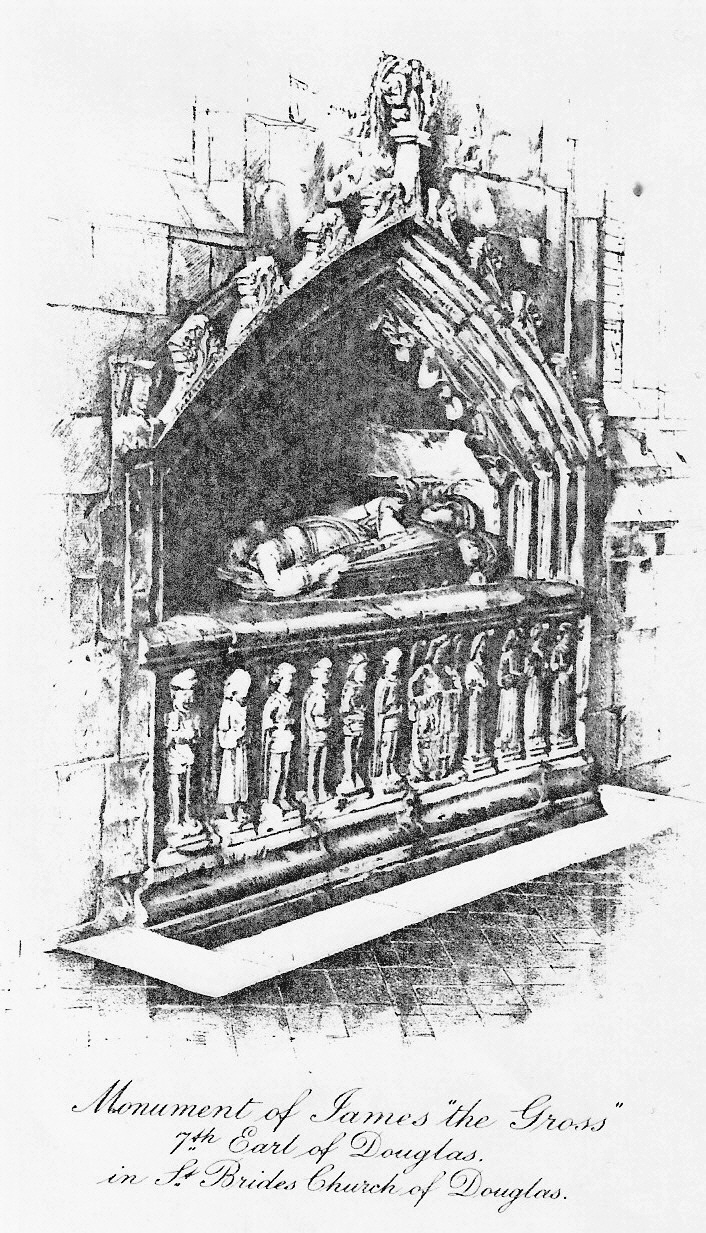

Abercorn Castle that Douglas died on 10 March 1443. His grossly fat

body, which earned him his nickname and which at his death

reportedly contained 4 stone of tallow, was buried in a magnificent

tomb in St Bride's Church in Douglas.

In spite of his career as a royal councillor it

is significant that, as seventh earl of Douglas and lord of

Lauderdale, James concentrated on family aggrandizement, leaving

custody of the king to Crichton and Livingston. The new Douglas earl

sought to create a network of lands and alliances which was not

limited to the southern interests of his predecessors. He directed

his younger sons towards north-east Scotland. His third son,

Archibald, was married to Elizabeth Dunbar, coheir of the earldom of

Moray, and in 1442 was created earl of Moray. Archibald's twin

brother, James Douglas, the

future ninth earl of Douglas, was chosen as bishop of Aberdeen in

1441, a mark of his father's influence with the conciliar party,

though the appointment proved ineffective; after the elder James's

death his two youngest sons, Hugh and John, were provided for from

his own northern estates. Earl James clearly intended to implant the

Douglas family into the disturbed political society of the north. In

the south he followed a similar course. In Berwickshire he

intervened in a complex feud within the Hume family. His principal

aim was to re-establish the influence exercised by his brother in

the east march before 1424. James did not ignore the traditional

territorial interests of the Black Douglases. Before his death he

probably arranged the marriage of his eldest son, William, future

eighth earl of Douglas, to Margaret, sister of William, the sixth

earl. To achieve this he had to obtain a papal dispensation. Through

this match Galloway, which James did not inherit, would be reunited

with the earldom. By inclination and experience, Douglas was not a

border magnate like his predecessors. His main residences at

Abercorn and Lanark confirm him as a magnate whose lands and

personal connections centred on Clydesdale and Lothian. The

marriages of his daughters to landowners in these two sheriffdoms

support this impression. It was thus appropriate that it was at

Abercorn Castle that Douglas died on 10 March 1443. His grossly fat

body, which earned him his nickname and which at his death

reportedly contained 4 stone of tallow, was buried in a magnificent

tomb in St Bride's Church in Douglas.

Douglas's career as

earl was one of superficial success. Family aggrandizement created

enemies, including Crichton, Bishop James Kennedy, and the earls of

Angus, without any secure increase in Douglas power. Relative

neglect of the family's place in the marches loosened loyalties

already shaken by the ‘Black Dinner’. Finally, by centring his

interests on Lothian, a heartland of royal interests, Earl James

risked future conflict with James II. Douglas's career had parallels

with that of his father. Both combined roles as royal servants,

family councillors, and ambitious and forceful magnates, and both

their long careers culminated in the acquisition of the Douglas

earldom. But the 1440s were not the 1390s. Changes in Scottish

political society and attitudes meant that the achievements of James

Douglas would leave his sons a difficult legacy.

Father: Archibald the Grim (3rd

Earl of Douglas) Douglas b: ABT. 1346

Mother: Joan\Johana (of Strathearn) Moray b: ABT. 1350

Marriage: Beatrix Sinclair, daughter of Earl of Orkney

- Married: BEF. 7 MAR 1424/25 in Orkney, Scotland.

Children

- William 8th Earl of Douglas b: ABT. 1425

- James 9th Earl of Douglas

b: ABT. 1440

- Archibald (Earl of Moray) Douglas

- Hugh (Earl of Ormond) Douglas, Executed in 1455

- John (Lord of Balveny) Douglas

- Margaret Douglas = Henry Douglas, son of

Sir

James Douglas,1st Lord Dalkeith

- Henry Douglas

- George Douglas

- Beatrice Douglas = William (1st Earl of Erroll) 2nd Lord Hay

- Elizabeth Douglas = Adam (of Craigie) Wallace (or William?)

- Janet Douglas b: 1398 in Brechin, Lanarkshire, Scotland = Sir Robert, 1st

Lord Fleming

Born 1371, he died at Abercorn in 1444.

See also:

• Standoff at

Tantallon Castle

Any contributions will be

gratefully accepted

Errors and Omissions

|

|

The Forum

|

|

What's new?

|

|

We are looking for your help to improve the accuracy of The Douglas

Archives.

If you spot errors, or omissions, then

please do let us know

Contributions

Many articles are stubs which would benefit from re-writing.

Can you help?

Copyright

You are not authorized to add this page or any images from this page

to Ancestry.com (or its subsidiaries) or other fee-paying sites

without our express permission and then, if given, only by including

our copyright and a URL link to the web site.

|

|

If you have met a brick wall

with your research, then posting a notice in the Douglas Archives

Forum may be the answer. Or, it may help you find the answer!

You may also be able to help others answer their queries.

Visit the

Douglas Archives Forum.

2 Minute Survey

To provide feedback on the website, please take a couple of

minutes to complete our

survey.

|

|

We try to keep everyone up to date with new entries, via our

What's New section on the

home page.

We also use

the Community

Network to keep researchers abreast of developments in the

Douglas Archives.

Help with costs

Maintaining the three sections of the site has its costs. Any

contribution the defray them is very welcome

Donate

Newsletter

If you would like to receive a very occasional newsletter -

Sign up!

Temporarily withdrawn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|