Coat of arms

WORK IN PROGRESS

Coat of arms

A

coat of armsA

coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon

or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to

identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour",

because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth.

(Image, left:

Archibald Douglas 'Bell the Cat', 5th Earl of Angus) The

coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full

heraldic achievement which consists of shield, supporters, crest and

motto. The design is a symbol unique to an individual person, and to

his family, corporation, or state. Such displays are commonly called

armorial bearings, armorial devices, heraldic devices, or simply

armorials or arms.

A

coat of armsA

coat of arms is a unique heraldic design on a shield or escutcheon

or on a surcoat or tabard used to cover and protect armour and to

identify the wearer. Thus the term is often stated as "coat-armour",

because it was anciently displayed on the front of a coat of cloth.

(Image, left:

Archibald Douglas 'Bell the Cat', 5th Earl of Angus) The

coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full

heraldic achievement which consists of shield, supporters, crest and

motto. The design is a symbol unique to an individual person, and to

his family, corporation, or state. Such displays are commonly called

armorial bearings, armorial devices, heraldic devices, or simply

armorials or arms.

Historically, armorial bearings were first

used by feudal lords and knights in the mid-12th century on

battlefields as a way to identify allied from enemy soldiers. As the

uses for heraldic designs expanded, other social classes who never

would march in battle began to assume arms for themselves.

Initially, those closest to the lords and knights adopted arms, such

as persons employed as squires that would be in common contact with

the armorial devices. Then priests and other ecclesiastical

dignities adopted coats of arms, usually to be used as seals and

other such insignia, and then towns and cities to likewise seal and

authenticate documents. Eventually by the mid-13th century,

peasants, commoners and burghers were adopting heraldic devices. The

widespread assumption of arms led some states to regulate heraldry

within their borders. However, in most of continental Europe,

citizens freely adopted armorial bearings.

Despite no

widespread regulation, and even with a lack in many cases of

national-level regulation, heraldry has remained rather consistent

across Europe, where traditions alone have governed the design and

use of arms. Unlike seals and other general emblems, heraldic

achievements have a formal description called a blazon, expressed in

a jargon that allows for consistency in heraldic depictions.

In the 21st century, coats of arms are still in use by a variety of

institutions and individuals; for example, universities have

guidelines on how their coats of arms may be used, and protect their

use as trademarks. Many societies exist that also aid in the design

and registration of personal arms, and some nations, like England

and Scotland, still maintain to this day the mediæval authorities

that grant and regulate arms.

Escutcheon (shield)

In heraldry, an escutcheon is a shield which forms the main or focal

element in an achievement of arms. The word is used in two related

senses.

Firstly, as the shield on which a coat of arms is

displayed. Escutcheon shapes are derived from actual shields used by

knights in combat, and thus have varied and developed by region and

by era. As this shape has been regarded as a war-like device

appropriate to men only, British ladies customarily bear their arms

upon a lozenge, or diamond-shape, while clergymen and ladies in

continental Europe bear theirs on a cartouche, or oval.

The Shield of Douglas is a characteristic example of the gradual

development of armorial composition. About A.D. 1290, the Seal of

William, Lord Douglas, displays his Shield, No. 155, bearing—Arg.,

on a chief az. three mullets of the field. Next, upon the field of

the Shield of William, Lord Douglas, A.D.1333, there appears, in

addition, a human heart gules, as in No. 156. And, finally, the

heart is ensigned with a royal crown, as in No. 157, this form

appearing as early as 1387.

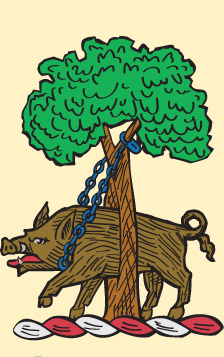

The

Boar is an animal which, with its parts, will constantly be met with

in British armory (Figs. 353-355). Theoretically there is a

difference between the boar, which is the male of the domestic

animal, and the wild boar, which is the untamed creature of the

woods. Whilst the latter is usually blazoned as a wild boar or

sanglier, the latter is just a boar; but for all practical purposes

no difference whatever is made in heraldic representations of these

varieties, though it may be noted that the crest of Swinton is often

described as a sanglier, as invariably is also the crest of Douglas,

Earl of Morton [" A sanglier sticking between the cleft of an

oak-tree fructed, with a lock holding the clefts together all

proper"]. The boar, like the lion, is usually described as armed and

langued, but this is not necessary when the tusks are represented in

their own colour and when the tongue is gules. It will, however, be

very frequently found that the tusks are or. The "armed," however,

does not include the hoofs, and if these are to be of any colour

different from that of the animal, it must be blazoned "unguled" of

such and such a tincture. Precisely the same distinction occurs in

the heads of boars (Figs. 356-358) that was referred to in bears.

The real difference is this, that whilst the English boar's head has

the neck attached to the head and is couped or erased at the

shoulders, the Scottish boar's head is separated close behind the

ears. No one ever troubled to draw any distinction between the two

for the purposes of blazon, because the English boars' heads were

more usually drawn with the neck, and the boars' heads in Scotland

were drawn couped or erased close. But the boar's head in Welsh

heraldry followed the Scottish and not the English type. Matters

armorial, however, are now cosmopolitan, and one can no longer

ascertain that the crest of Campbell must be Scottish, or that the

crest of any other family must be English; and consequently, though

the terms will not be found employed officially, it is just as well

to distinguish them, because armory can provide means of such

distinction--the true description of an English boar's head being

couped or erased "at the neck," the Scottish term being a boar's

head couped or erased "close."y a boar's head

will be stated to be borne erect; this is then shown with the mouth

pointing upwards. A curious example of this is found in the crest of

Tyrrell: "A boar's head erect argent, in the mouth a peacock's tail

proper."

The

Boar is an animal which, with its parts, will constantly be met with

in British armory (Figs. 353-355). Theoretically there is a

difference between the boar, which is the male of the domestic

animal, and the wild boar, which is the untamed creature of the

woods. Whilst the latter is usually blazoned as a wild boar or

sanglier, the latter is just a boar; but for all practical purposes

no difference whatever is made in heraldic representations of these

varieties, though it may be noted that the crest of Swinton is often

described as a sanglier, as invariably is also the crest of Douglas,

Earl of Morton [" A sanglier sticking between the cleft of an

oak-tree fructed, with a lock holding the clefts together all

proper"]. The boar, like the lion, is usually described as armed and

langued, but this is not necessary when the tusks are represented in

their own colour and when the tongue is gules. It will, however, be

very frequently found that the tusks are or. The "armed," however,

does not include the hoofs, and if these are to be of any colour

different from that of the animal, it must be blazoned "unguled" of

such and such a tincture. Precisely the same distinction occurs in

the heads of boars (Figs. 356-358) that was referred to in bears.

The real difference is this, that whilst the English boar's head has

the neck attached to the head and is couped or erased at the

shoulders, the Scottish boar's head is separated close behind the

ears. No one ever troubled to draw any distinction between the two

for the purposes of blazon, because the English boars' heads were

more usually drawn with the neck, and the boars' heads in Scotland

were drawn couped or erased close. But the boar's head in Welsh

heraldry followed the Scottish and not the English type. Matters

armorial, however, are now cosmopolitan, and one can no longer

ascertain that the crest of Campbell must be Scottish, or that the

crest of any other family must be English; and consequently, though

the terms will not be found employed officially, it is just as well

to distinguish them, because armory can provide means of such

distinction--the true description of an English boar's head being

couped or erased "at the neck," the Scottish term being a boar's

head couped or erased "close."y a boar's head

will be stated to be borne erect; this is then shown with the mouth

pointing upwards. A curious example of this is found in the crest of

Tyrrell: "A boar's head erect argent, in the mouth a peacock's tail

proper."

Woodward mentions three very strange coats of arms

in which the charge, whilst not being a boar, bears very close

connection with it. He states that among the curiosities of heraldry

we may place the canting arms of Ham, of Holland: "Gules, five hams

proper, 2, 1, 2." The Verhammes also bear: "Or, three hams sable."

These commonplace charges assume almost a poetical savour when

placed beside the matter-of-fact coat of the family of Bacquere:

"d'Azur, à un ecusson d'or en abîme, accompagné de trois groins de

pore d'argent," and that of the Wursters of Switzerland: "Or, two

sausages gules on a gridiron sable, the handle in chief."

|

|

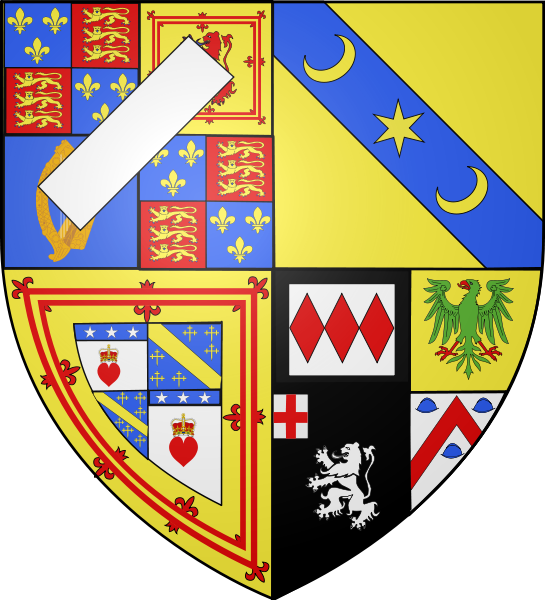

The coat of arms (above) of the 5th Duke of Buccleuch, is made up of the following heraldic charges:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bend

between |

Bend, on

a, between |

Bordure |

Chief, on

a |

Coronet,

ducal, out of |

Crescents

(2) |

Cross

crosslets (6) |

Crown,

imperial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| eagle

displayed |

France

and England |

Heart |

Lozenges |

Mullet |

Mullets

(3) |

Stag

trippant |

|

Any contributions will be

gratefully accepted

Errors and Omissions

We are looking for your help to improve the accuracy of The Douglas

Archves

If you spot errors, or omissions, then please do

let us know.

The Forum

If you have met a brick wall with your research, then posting a

notice in the Douglas Archives Forum may be the answer. Or, it may

help you find the answer!

You may also be able to help others answer their queries.

Visit the

Douglas Archives Forum.

What's New?

We try to keep everyone up to date with new entries, via our

What's New section on the

home page.

We also use

the blog to keep researchers abreast of developments in the

Douglas Archives.